Dan Asia Appeciation

7/7/2014

Final Alice is a series of elaborate arias, interspersed and separated by dramatic episodes from the last two chapters of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, centering around the Trial in Wonderland (which gradually turns to pandemonium) and Alice's subsequent awakening and return to 'dull reality.' To this I have added an Apotheosis.

Final Alice teeters between the worlds of opera and concert music. It is, on the one hand, opera-like in its dramatic continuity, its arias, its different characters. On the other hand, it is a Grand Concerto for voice and orchestra, as a single person must perform all these various functions (maintaining then the familiar concert hall confrontation between soloist and orchestra). If I were to invent a category for it, I would call Final Alice an 'Opera, written in Concert Form.'

Of the poems used, only texts of Arias I, II and V are by Lewis Carroll (and only the poem of Aria I appears in the Alice story). Arias II and IV are the Victorian originals. The relationship between these parodies and originals I found particularly intriguing and ultimately inspiring. Arias I and II are not only Carroll texts, but also two version of the same poem: Aria II is an earlier version not appearing in Alice. Both share the same world of confused pronouns and very little sense. Further, they first line of Aria II copies the first line of Alice Gray, a sentimental song by William Mee that was popular at the time. 'Did Carroll introduce Mee's poem into the story because the song behind it tells of the unrequited love of a man for a girl named Alice?' So queries Martin Gardner in a footnote from his book 'The Annotated Alice.' Aria IV, 'Still more Evidence,' an extended setting of the poem Alice Gray, is my answer. What moved me here was the desire not just to set the words 'at face value,' but rather to capture and convey the feelings those words must have aroused in the breast of the shy Oxford don. 'Disillusioned,' the second Victorian original, imitates closely the meter of Alice Gray, but grotesquely distorts and mocks its sentiment. It is a cracked mirror-image; a devil's version of the angels' Alice. These two poems, Alice Gray and Disillusioned, are set side by side to music of the most violent contrast, as Aria III, 'Contradictory Evidence.'

Aria V is a setting of the concluding poem from the second Alice book, Through the Looking Glass. This poem is an acrostic, the initial letters of the lines spelling out the name of the 'real' Alice (ALICE PLEASANCE LIDDELL).

Final Alice tells two stories at once; primary is the actual tale of Wonderland itself, with all its bizarre and unpredictable happenings. All of these are painted as vividly as possible. But 'reading between the lines,' as it were, is the implied love story of Lewis Carroll and Alice Liddell, as suggested by the poems Alice Gray and the Acrostic Song. By introducing these additional poems into the Trial as depositions of evidence, given by the White Rabbit (acting as a kind of chief prosecutor), I wished to bring that love story closer to the surface — not so much as to disturb the amusing, eccentric, sometimes terrifying story as it goes on and on in its inexorable fashion — but enough to leave a recognition; to add what one might call the human dimension of the man, seen only intermittently to be sure, but (one hopes) always affectingly, perhaps lingering in memory after the dream of Wonderland itself has faded.

Guilty pleasures. Serious fun. Heavy entertainment: It's hard to know what to call the National Symphony Orchestra's program last night. It was filled with music that many people might dismiss as light, or even in bad taste: Paganini's Violin Concerto, written as a showpiece for a flashy virtuoso, and David Del Tredici's hour-plus "Final Alice," as untrammeled and in-your-face as a piece of orchestral music can get.

Yet the concert was utterly intense and compelling. Many classical music fans will readily believe that the violinist Hilary Hahn can make something breathtaking out of the Paganini, but they may not be prepared for a dramatic reading of the last two chapters of "Alice in Wonderland," performed with ceaseless energy and stratospheric high notes by a soprano who appears to be channeling Lucia di Lammermoor on acid. Believe me, the latter is as much worth hearing as the first.

The orchestra began with the Overture to Verdi's "I Vespri Siciliani" to signal that this was to be an evening of entertainment. But there is no need to consider the overture too carefully; the orchestra certainly didn't. It showed the eager, sloppy energy of a dog that leaps when a ball is thrown, but then turns in circles to figure out where the ball has landed: There were a lot of fractured entrances with chords that took a minute to come into focus.

Hahn then made her entrance in a black dress with decollete that reached nearly to her navel. I would not mention the soloist's dress had it not so well matched the piece she played, and the way she played it. On most women, that dress would have appeared provocative, vulgar; on Hahn it epitomized cool and classic elegance. By the same token, she took Paganini's showy and probably vulgar piece and treated it as if it were the finest music, and as if her prodigious feats of violin playing were all in its service.

I personally am a recent Hahn convert (though plenty of listeners could have told me my error long ago), so perhaps I speak with a convert's zeal: Her control over the instrument last night was jaw-dropping. She held a singing legato all through Paganini's leaps and double-stops and Italian-opera-style figurings, and in the cadenza she put all that aside and wove her own delicate net around the long lines of the music. When it was over, called back by applause, she offered a pure, clean, honest reading of the Sarabande from Bach's Second Partita; it says a lot about the way she played the Paganini that the Bach seemed a complement rather than a departure.

And then: "Final Alice." It was written in 1976, and is in a way a psychedelic relic of its time, with lots of wild, luscious orchestral colors (including a theremin uttering its horror-movie "woowoowoo" sound effect at Alice's unpredictable growth spurts) to illustrate Lewis Carroll's inimitable dreamscape. It is easy to forget today that composers who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s felt constrained to write in a particular kind of intellectual academic style, and with this piece Del Tredici is not merely throwing off those constraints, but giving the whole style the figurative raspberry. The work's tonal passages are less the issue than its sprawling, glorious self-indulgence: its obsessive focus on a forbidden love (the tacit fixation on the figure of Alice is at its heart); its length; its flashes of quotation (was that a big band? do I hear Ravel's "La Valse"?); and even, at the end, the composer's signature, when the soprano counts, in Italian, the chimes of miniature cymbals, until she reaches the 13th, when the whole orchestra whispers "Tredici!"

The piece is a tour de force, in all its sprawling zany length, though it is certainly not everyone's cup of tea. Music Director Leonard Slatkin deserves kudos for bringing it back in its uncut length for its first performance in decades. Equal praise is owed to the soprano Hila Plitmann for pulling off a work that has her onstage, alternately speaking, singing at stratospheric heights and screaming into a bullhorn for more than an hour. Since I have broken a taboo and spoken of dresses, I should mention Plitmann's, topped with a tulle-and-flower skirt that made her look like a cross between a flower child and Dickens's Miss Havisham, and somehow like Alice at the same time. She has a wonderful speaking voice, sings like an angel (Del Tredici's arias are like hyper bel canto; his main theme echoes an ornament from "Caro ome" in Verdi's "Rigoletto") and squeals like a guinea pig when the text compels her to do so. If this doesn't pique your interest, nothing will.

There are two more performances of this program, tonight and tomorrow night: Go, and prepare to enjoy yourself, but fasten your seat belt.

It was the most outrageous thing the music establishment could have imagined. Here was Sir Georg Solti leading the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in a new work by a leading avant-garde composer, and there were . . . arias! With actual melodies! Contemporary music, as everyone knew, was supposed to be thorny and atonal stuff, with no use for the outdated conventions of the past. Yet here was bar after bar of lush, unrepentant harmony, hummable tunes, symphonic gestures right out of Mahler. Even a fugue.

To the ruling avant-garde it was a slap in the face -- and as a final insult, the audience leapt to its feet, cheering, when the piece came to a close.

It was Oct. 7, 1976, and the work was "Final Alice" by 39-year-old composer David Del Tredici. Until that moment, he'd been a card-carrying member of the avant-garde. But in one bold stroke, Del Tredici jettisoned the strict composing system known as serialism (which dominated new American music, to the despair of most audiences) and embraced a neo-romantic style -- scandalizing his colleagues and setting off an earthquake in American music whose aftershocks are still being felt.

" 'Final Alice' changed the face of music in this country overnight," recalls Leonard Slatkin, the National Symphony Orchestra's music director, who was in the Chicago audience that night. "It destroyed all conceptions of what 'new music' was supposed to be, and many composers will tell you that they were now liberated to write how they felt. It was the start of a revolution."

Slatkin is bringing the complete work to the Kennedy Center for the first time this weekend, and it promises to be a spectacle. A sort of opera in concert form, "Final Alice" is drawn from Lewis Carroll's "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" and is just as wildly imaginative as the original. Spoken and sung by an amplified soprano (the remarkable Hila Plitmann, in her NSO debut) who at one point sings through a bullhorn, it calls for a gargantuan orchestra augmented by sirens, a theremin and an amplified "folk group" of saxophones, a mandolin, a banjo and an accordion.

"It's a retro piece in the aspects of melody and harmony and rhythm -- literally a return to tonality," Slatkin says. "But the sounds are just insane." And that's probably appropriate for the plot of "Final Alice," which focuses on the last two chapters of Carroll's book. It tells the story of an edgy, nonsensical trial (someone stole some tarts) that starts out lightheartedly but ratchets steadily into pandemonium, until the Queen shouts "Off with her head!" -- and Alice wakes back in reality.

But it wasn't the story that intrigued Del Tredici as much as the story behind the story. The Alice-in-Wonderland tale, as is well known, was actually written by the Rev. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a respected English mathematician and logician. Greatly taken with a young girl named Alice Pleasance Liddell, he made up the tale for her and her sisters, publishing it in 1865 under the pen name Lewis Carroll. With its puns, logic games and engagingly absurd rhymes, the book became a classic of children's literature. But there have long been disturbing questions about Dodgson's relationship with Alice Liddell. He clearly was infatuated with the child, and -- while there's no solid evidence that he was a pedophile -- Dodgson was known to be extremely interested in young girls, avidly searching them out, befriending them, even taking nude photographs of them. The Liddell family eventually broke off relations with him, for reasons never fully explained.

And yet, while scholars agree that Dodgson was almost certainly in love with Alice (there's a persistent rumor that he proposed marriage to her in 1863, when she was all of 11), he seems to have repressed any sexual feelings he may have had. "He probably felt more than he dared acknowledge, even to himself," biographer Morton N. Cohen has suggested.

That story of forbidden love caught Del Tredici's imagination.

"What inspired me to do 'Alice' was partly Lewis Carroll, and partly Martin Gardner, who wrote 'The Annotated Alice,' " says the New York-based composer, now 71. Gardner's 1960 book showed that many of Carroll's nonsense verses were based on popular songs of the day, and pointed to secret meanings in the work. Particularly interesting was a love song called "Alice Gray," by William Mee, about a man's unrequited passion for a girl named Alice.

"I wanted to put in the true story of Carroll," Del Tredici says. "His love for Alice, whatever it was. And since these were forbidden poems -- the truth, let's say, about Carroll -- I would set them in the forbidden language, which at that time was, of course, tonality. So in a way I use the tonality in 'Final Alice' as a metaphor -- an image of 'forbiddenness' unveiled."

Metaphor or not, the leap into tonality was a bold move. Composers in the 1970s saw themselves as being in the vanguard of a revolution, forging a new musical language built on the 12-tone system of Arnold Schoenberg. Tonality belonged to the past, and audiences were treated as almost irrelevant. "Who Cares if You Listen?" asked Milton Babbitt, one of the leading serialists of the day, in the title of a celebrated essay.

"It was inconceivable at the time to write tonally," Del Tredici says. "I thought, I cannot do this -- my colleagues will think I'm nuts! But I realized that my instinct had given me these tonal chords with the same excitement it used to give me minor ninths and minor seconds, so I decided to go with my instinct. I went back and finished the piece and hoped for the best."

And the music is revelatory. The words of the innocent, sweeping aria that opens the work are right from the book. But as the drama unfolds, the singing gets increasingly edgy and tormented. New texts are introduced, the arias swell with anguish, and as the lid is torn from Carroll's secret love, the music explodes. Tempos leap madly around, the theremin wails, sirens shriek, and the soprano hurtles herself against the furthest reaches of her range. From light, amusing children's fantasy, "Final Alice" turns into something much different -- a gripping portrayal of turmoil in the human heart.

The work was a popular triumph, and it shot Del Tredici into the limelight. ("Before 'Final Alice,' I was a respected composer," he says. "After it, I was either loved or hated.") Solti recorded it, and a subsequent commission from Slatkin resulted in 1980's "In Memory of a Summer Day," which won the Pulitzer Prize. A major shift toward tonality had begun in American music, launched almost single-handedly by "Final Alice."

But even as neo-romanticism settled firmly into the American musical mainstream -- marked by such works as Mark Adamo's "Little Women" -- Del Tredici kept pushing at the edges. Like Carroll, he had his own demons, and after winning the Pulitzer he went through what he calls "a kind of personal breakdown" marked by alcoholism and sex addiction. Fighting his way back into balance, he says, changed his identity as a composer.

"Coming out of that breakdown brought me some personal exploration, and that got me into being out about being gay," he says. "I'd always been personally out as a gay man, but to actually make it a public expression of my music -- I would never have done that unless I felt I had somehow crashed and come back."

The result has been a string of works as shocking in their own way as "Final Alice" was -- songs celebrating gay life, often built around pornographic texts by writers such as Allen Ginsberg. It's a controversial path, but Del Tredici says he needs to trust his instincts -- the same ones that brought him so famously to tonality -- even if they result in music considered too outrageous to be widely performed.

I often get tarred for my passions, but I feel I have no choice: Music is passionate to me," he says. "And music is about passion, no matter how much to the contrary in the 20th century we may have been told."

So he's become a maverick once again?

"Yes!" the composer says, laughing. "In my 70s, I'm still being a bad boy."

People rarely associate classical music with being sexy. Even with the cello being nicknamed "the lover's instrument," there's a certain stuffy atmosphere to the genre — one that Pulitzer Prize-winning, gay composer David Del Tredici likes to shake up.

""There's so much prudery in classical music," says Del Tredici. "It annoys me."

The composer, whose mega-work "Final Alice," will be played in its entirety for the first time in over 30 years by the National Symphony Orchestra, has been pushing the boundaries of the classical music establishment for decades.

"Final Alice," a piece with narration, orchestra and singing, uses the writings of Lewis Carroll as a context for the piece, wherein Del Tredici focuses on the relationship of the author (real name: Charles Lutwidge Dogdson) with a little girl acquaintance, Alice Pleasance Liddell.

Much of the seeming nonsense verse of the "Alice in Wonderland" stories are actually parodies of popular Victorian songs, and Del Tredici interwove the original songs and Carroll's versions in the 1976 composition.

"Some of the models for the trial scene were simple songs which spoke of the love of a man for a girl named Alice," says Del Tredici. "In many ways, they're hiding the real truth. That made me really interested in the love story of Alice and Carroll."

Exploring — what scholars debate as — the forbidden love Carroll held for Alice, Del Tredici chose to match the metaphor of underground love in his music — most notably by using tonality. The classical music world at the time was obsessed with atonality, and Del Tredici's groundbreaking work helped to usher in an era of Neo Romanticism in the genre.

DEL TREDICI CONTINUES to dive into verboten territory, including setting a number of erotically charged gay literary works to music, the most recent examples being "Queer Hosannas" and "A Field Manual," both performed for the first time this month.

"I realized there is no gay body of music, and the way to make music gay was to set explicitly gay poetry," he says. "I like it to be explicitly erotic and even pornographic and very

gay."

The "Queer Hosannas" consist of works by three different poets, and "A Field Manual" is a setting of five different poems by gay poet Edward Field, whom Del Tredici knows well.

"We live in the same building," Del Tredici says, adding that the poetry for "Field Manual" is "very out, very naughty."

Sexual expression is a theme that runs throughout much of the composer's canon and day-to-day life. He met his partner of eight years, Ray Warman, at a workshop produced by the Body Electric, an organization that offers workshops on eroticism all over North America.

"It's the only group that dares to use sexual energy for healing," Del Tredici says. "It had the effect on me somehow of making me lose creative self-consciousness. I've written much quicker and more fluently. The idea of Eros and creativity being connected is true."

Del Tredici also says that gay sexuality has a profound influence on a composer's work.

"I think gay composers in particular are attuned to being expressive. Look at the distinguished list of gay American composers — [Aaron] Copeland, [Samuel] Barber, [Gian Carlo] Menotti, [Leonard] Bernstein. I think the significant thing is that a gay composer has known alienation very personally — certainly in my generation, it couldn't be more forbidden."

Final Alice is an exhilarating experience — a brilliant gallimaufry of sounds, effects and techniques from just about everywhere — yet it sounds like the music of nobody else.

It's hard to realize that David Del Tredici turned 70 last year, A perennial "bad boy" of new music, he's retained his edge, playfulness, and subversive combination of decadence and innocence.

These two discs make a fitting, if belated, birthday present.

The big news is the return of Final Alice (1976) to the discography. Del Tredici named it that because it sets the conclusion of Alice in Wonderland (at the time it also seemed it would be the last in his series of settings of that book, but he‘s returned to it numerous times since). Final Alice is really unlike anything before it, though it has sure roots. The most important is the revival of a lost tradition, that of melodrama, the art of a sung theater piece in a concert setting. As a one-woman bravura show, it asks the singer to take on all the roles of the characters and be narrator; to both speak dramatically and sing at fever pitch for almost an hour, non-stop; and to switch styles on a dime, from music hall to slapstick to grand opera. By the end the chaos is so overwhelming she has to whip out a bullhorn to compete.

Del Tredici had already gained notoriety as a trained serialist who threw it all away to embrace a lush, indulgent neo-Romantic language, and many have never forgiven him. But in retrospect it was absolutely the right move. For one thing, it was him, the music took on enormous honesty. And along with George Rochberg and William Bolcom, he helped to invent American musical postmodernism, which has never been as ironic and academic as its counterpart in the visual arts. Subversive always, but all three of these composers have never abandoned their hearts in order to write this music that reshuffles all the sources and questions our relation to them.

Final Alice I think is a masterpiece. I still get chills at the end, when the poignant "Acrostic Song" (very Elgaresque) unspools, with the orchestra chanting the first letter of each line, which spells out the name Alice Liddell. I now hear it as an authoritative tribute and send-up to Ronsenkavalier, and I keep discovering things I didn't notice at first (like the oboe tuning A that starts the piece, and is the last note/sound in the entire work). While some have criticized the piece as being reactionary, in fact nothing could be farther from the point. It is music that could have only been written at its historical moment. Its sheer craziness, chaotic theatricality, and love/death embrace of tonality is part and parcel of America in the 1980s. And it's perhaps the definitive approach to the sweetness and terror of the original text.

The Innova disc presents a pair of chronological bookends to Final Alice. Vintage Alice dates from 1972, and sets the famous Mad Hatter's Tea Party scene (the title has nothing to do with Carroll, coming instead from the Paul Masson Winery‘s commission). Obsessively focused on the tunes Twinkle, twinkle little star and God Save the Queen, it uses even more experimental techniques than Final Alice in particular, polytonality and poly-tempos. As in Final Alice, there's a folk group, and the singer narrates, takes all the roles, and moves into extremes of repetition and register. In a sense, it feels like a dress rehearsal for its longer, more ambitious descendent.

Dracula is from 1999, and sets a prose poem by Alfred Corn, "My Neighbor the Count," which relates a tale of progressive seduction, debasement, and enslavement of the narrator by the eponymous vampire, all from her victim's viewpoint. It has a brilliant, day-glow orchestration, cinematic in its high definition and bright colors. It uses the theremin near its conclusion as an aural symbol of the union between victim and oppressor. The piece is both funny and scary. Del Tredici treads a very narrow path here between camp and compassion, and for my money he pulls it off. Only the very ending feels a little unfulfilling after the long buildup, but it doesn't fatally undercut the overall impact of the whole work.

Soprano Hila Plitmann is a knockout in both pieces. She's a worthy successor to Hendricks. She has the sort of fluency of so many great young American singers nowadays, which allows her to switch effortlessly from speech to naturalist theatrical singing, to full operatic aria, to more experimental extended techniques. Her acting skills are extensive and often hilarious, as she deftly impersonatcs the Mad Hatter, the Dormouse, and Count Dracula. There was a wonderful recording on the DG "20/21" series of Vintage Alice with Lucy Shelton, Oliver Knussen, and the ASKO Ensemble, but it's already out of print, so lnnova's is now the work's sole representative, and does have the advantage of the composer as conductor.

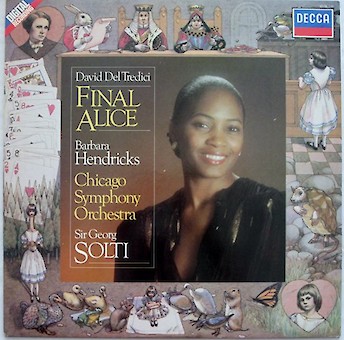

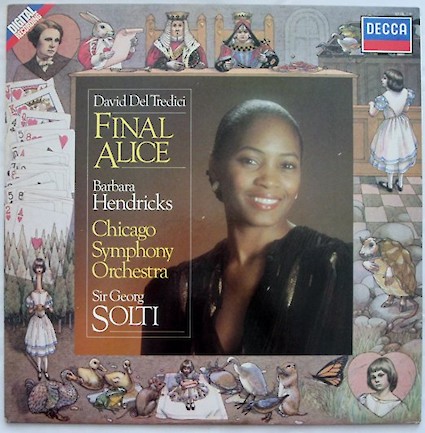

The Decca release of Final Alice is a reissue of the original LP, and it's hard to imagine this performance will ever be bettered. Hendricks is spectacular, and the CSO never sounded more sonically Technicolor. Del Tredici shows that over three decades he's been able to keep his edge, and even though the music may have moved towards a slightly more Hollywood sound and presentation, it's still anything but comfortable, I have a feeling his is a body of work, which despite possessing an in-your-face quality for decades, is only now starting to come into clear focus. It simply cannot be categorized, yet fits seamlessly into a tradition – though which tradition may be up to you the listener to decide. But these are both a joy to behold, and Final Alice is now a strong contender for my Want List.

Piano and flute regretfully say goodbye at the end of Alice's fantastic dream, expressing the quiet hope that some of the magic of that vision might live on in the real world. These few minutes of enchantment are the high point of the disc.

7/7/2014

Composed in the 1980's, this is a refreshingly accessible major composition. The performance is magnificent, with Barbara Hendricks reading and singing the text adapted from the work of Lewis Carroll. The great Georg Solti leads the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (for which the work was comissioned) rousingly, and the sound is first-rate.